imagined shadow

I think I

see you on the

street half a

block ahead of me

you’re pointing at

the mountains or at

some blue green white

tile in the facade

or wall of an old

church you’re talking

to an old woman on

the street selling

sliced fruit topped

with tajin (chili

salt powder) or

listening to that

street musician

(violin) wondering

can you request

a piece you know

will he know the

Bach Partita you

stop and look in a

store window the

way in life you liked

to suddenly stop to

comment to a

stranger walking

by look at that

you say how’s about

them apples you ask

you turn suddenly

and from half a block

away I hear you

ask me what do you

think what do I

think I think I’ve

been thinking of

you of you I think

you are here in

southern Mexico

you’re walking these

streets in

shadow and miracle

creating shadow and

sound you’re walking

you’re breathing

you really don’t

do either anymore

and I think you’ll

visit me here the rest

of my life

—Mark Statman, from Hechizo (Lavender Ink/díalogos, 2022)

La sombra imaginada

Me parece verte

en la calle adelante

a media cuadra

estás señalando

las montañas o el mosaico

azul verde blanco

de una fachada

o del muro de alguna antigua

iglesia le hablas a una

una anciana que vende

frutas en rodajas

con Tajín (polvo de chile

y sal) espolvoreado encima o

estás escuchando a ese

músico callejero

(violín) preguntándote si

puedes pedirle

una melodía que conoces

si se sabrá la

Partita de Bach te

detienes y miras la

ventana de una tienda de la

manera en la que en vida

te gustaba detenerte

de repente para

comentarle a un extraño

que pasa mire eso

dices usted ¿qué

opina de eso? preguntas

te das la vuelta y

media cuadra adelante

escucho que me

preguntas y tú ¿qué

piensas? ¿que yo

qué pienso? Creo que

has estado en mis pensamientos

que en ti he estado pensando

pienso que estás aquí

en el sur de México

caminando por estas

calles entre sombras

y milagros proyectando sombra y

sonido estás caminando

respiras aunque realmente ya

no haces ninguna de las dos y

creo que me visitarás

por el resto

de mi vida.

—Mark Statman, Chicatanas: Breve Antología, version al español Efraín Velasco (Subpress International, 2023)

I love my influences. I love how I have depended on others. I love that I come from many big families. I seriously believe in the brotherhood and sisterhood of all of us.

A couple of posts ago, I wrote about El Día Internacional de la Mujer. I wrote about my mom. Some of you wrote me back about your moms. It was crazy great. Our moms.

If I made the list of all the fathers I could claim as inspiration, as mentors, as teachers, as coaches, as friends, it would divide out in normal ways. My list might surprise some, others not at all. Poets would see familiar names. Former classmates and students would as well. Whatever one does in life there’s always all these people. My names might get you thinking of names you would add. Your names would get me adding more and we could spend a lot of time like this.

Many fathers. I have many.

One dad.

Al Statman.

Hi Dad.

Seven years ago yesterday, my dad did what Shakespeare has Hamlet call shuffling off this mortal coil.

He didn’t disappear. In a certain way, he became more active, more vibrant.

I started to notice him more. I started to understand him better. I started to see my dad because of his absence .

We had established a thing in the last 10-15 years of our lives before he died. We talked almost every Sunday. During the baseball season, we would talk Yankees and Mets baseball. He was a big Yankees fan, I like the Mets. We both believe in the game, with all its funny rules, all the game’s stories. I always thought, all the anecdotes, his deep made for radio voice, he’d have been a great baseball broadcaster, color commentary.

During the football season, we would talk before the Sunday games started. We both cared a little; a NY football Giants fan his whole life, he had become a follower of the Arizona Cardinals after he moved to Surprise, AZ, just outside Phoenix. And me? After my youthful rebellion had driven me into the NY Jets camp, a prodigal son, I returned, and was there many years in Brooklyn holding down the football Giant fort.

Did we really talk about football? Baseball? Were we really talking about sports? A little, I think. But after a long time, and this has become clearer to me in the years since my dad died, he was using this time in a different way. My dad liked to tell me things. He didn’t seem very good about talking with me about things that mattered. Small talk? An Al Statman specialty. He was almost a master at it. But serious stuff? Not so often.

Except. He was saying things at the time I didn’t know I was hearing. He was explaining an outlook on life in which he always seemed to see the good in the world. How about them apples? He looked at life with a sense of wonder I know is esssential to me as a poet. Would they know the Bach Partita? But why wouldn’t they? The world he lived in was an incredible place.

My dad had a story for every occasion. He was always full of dad surprises. Driving into Quebec province—he bought a beret and annoyingly sang Frère Jacques over and over, giggling. Visiting my parents once in Arizona I rented a four-wheel drive SUV and he directed me to drive off-road. There was something he had to show me—one of the last herds of wild horses in the US. Look at those, he whispered.

One time, shortly after I started my freshman year at college, my dad met the man who had made sure I had a full fellowship to do my undergraduate work at Columbia, Charles Robespierre O’Malley (yes, Robespierre). Commenting on Mr. O’Mallley’s manner (yes, I called Mr. O’Malley Mr. O’Malley for all the years I knew him, even to this day decades later as I write this), my dad said, He’s the last of the real gentlemen.

What do you mean? My dad looked at me (and here, this is memory, but it feels as clear to me now as it did in 1976).

I don’t know him, he said. But from what I can tell? He cares about others. He’s smart. He’s likeable. He has no airs. He never makes anyone feel less than, never makes anyone feel they aren’t good enough. He admires courage. He admires clarity. He admires the truth. He’ll have your back always. He’s loyal. You’ll always be able to depend on him. No mattter what. He’s a decent man. He has dignity.

He’s a decent man. He has dignity.

A gentleman.

I’ve had the privilege and honor and joy of knowing some of the smartest people anyone could ever know in our time. Poets and painters. Doctors. Lawyers. Scientists. Life has gifted me this.

My dad’s parents were immigrants and he was a Stuy kid (New Yorkers know what that means: Stuyvesant High School? Genius). He was Air Force in Korea and Japan. He had graduate degrees from NYU. For decades he was an executive at The New York Times. I’m not sure how he’d feel about the Times these days, but he was very loyal. He liked working there because, a New Yorker to the core, he liked feeling he was in the center of things. And at the Times, he felt close to the whole world. A favorite story? Once he came home from work and at dinner mentioned he had ridden the elevator with Golda Meir, the Kyiv born, Wisconsin school-teacher, who became the Prime Minister of Israel in the late 60’s.

You rode the elevator with Golda Meir? What did you say to her?

He paused, looked a little self-important, and then gave that big Al Statman smile. I said, Shalom, Golda!

Does one ever see one’s father or mother or siblings the way others do? There’s too many lenses. Too much history. Too much stuff that can get in the way.

But I think back on what he said about Mr. O’Malley. And what he appreciated in Mr. O’Malley. How he appreciated those qualities because those were qualities he aspired to in himself.

There’s a lot of stuff going on in the world that’s pretty awful. There are too many people who are in positions of power who only care for power, who lack courage, conviction, who lie and cheat. Undependable cowards who have no idea about dignity and decency.

My dad was nothing like those creeps. Although my dad would never say it, our world needs more of my dads. My dad, Al Statman, who died seven years ago, was a gentleman.

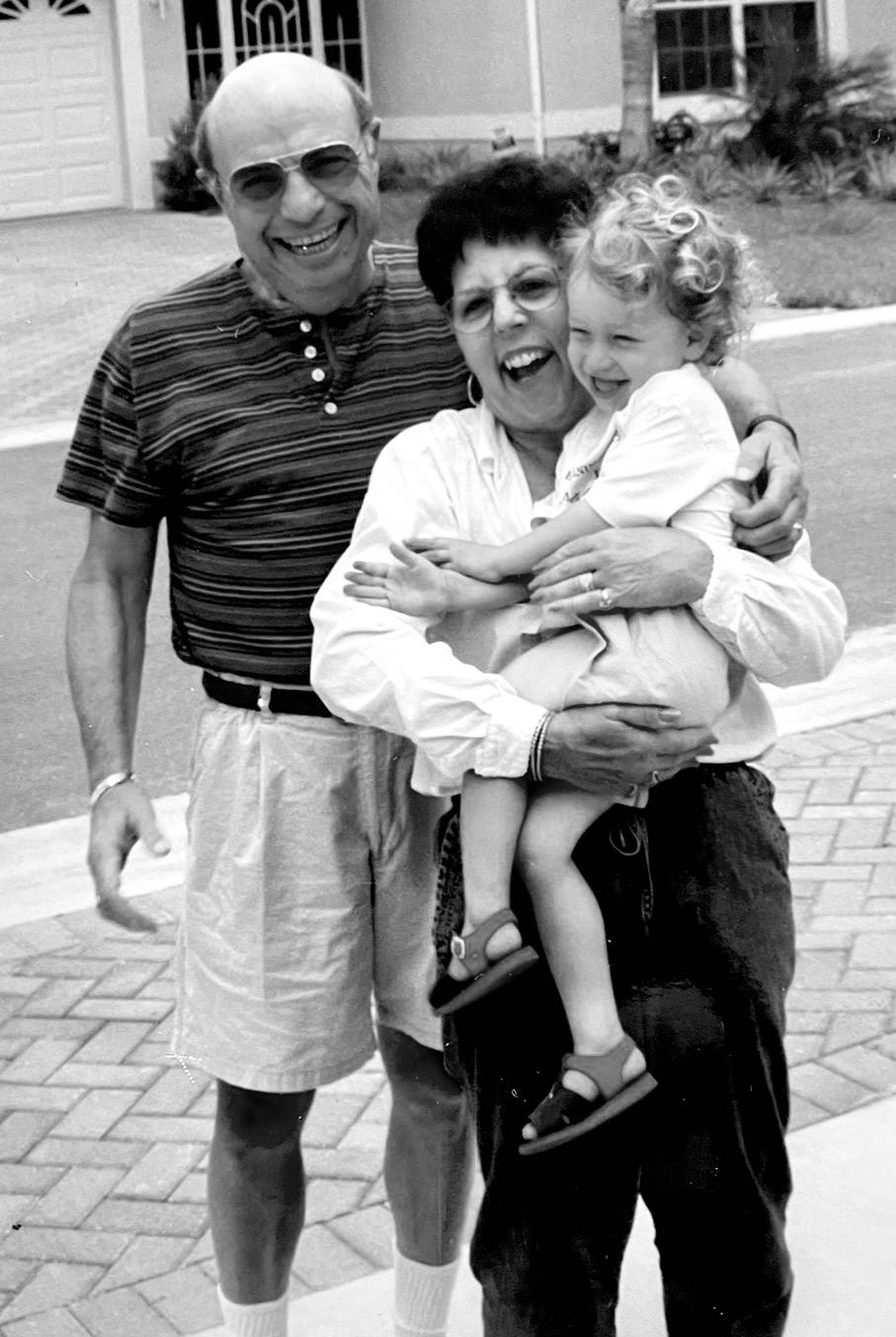

My mom and dad with grandson, Jesse, 1996.

erasing roads

no backwards look

mornings evenings

no in-between

silence no

mind no logic no

beauty of rising and

falling apart nowhere

more familiar than

the where of

desire the black of

blackbird

we love illusion

rain dust the

puddled road

accordion folded

corn rising from close

and farther fields my

father would have

loved this my mother

less so though I see

her watching while

he speaks with one

campesino after

another wondering

which story he’ll

tell it will depend

on what’s on

his mind today

my mind buzzes

heavenly questions my

mom my dad we’re

watching mountains

and my dad is at it

putting the story

together my mom

says my

tears will turn to

milk and honey my

dad says you won’t

believe what

that man said

—Mark Statman, from Volverse/Volver (Lavender Ink/diálogos, forthcoming April 1, 2025)

Good Links: Only one…

My dad loved Frank Sinatra and this was his favorite Sinatra song. The night of the morning before he died, he was at home—his decision to come home, to go on his own terms, no machines—my brother Russell played Sinatra singing My Way for him, and Dad, eyes closed, barely conscious, smiled and hummed along. The next afternoon—Katherine and I were staying in a hotel that gave out onto a park with fields—there was a fest going on. I went for a walk by it, a need in my grief to clear my head, and suddenly there was a mariachi band playing a mariachi My Way. My dad’s way of saying Here I am.

Thanks for this! THINK Journal just published a poem of mine about William James & about what I think of as a recent “sighting” of my brother, whom we lost in 2023. Those we’ve loved stay with us.

Thanks for sharing. I’ll have to go back and look for the article about your mother. I have a poetry place too, I am preparing to share memoir about my mom, who died 11 years ago. It’s taken me this long but now I’m ready to share her with the world. She was amazing.

My dad is around and I am enjoying getting to know him more now that mom isn’t around. She was the big talker… but now I’m hearing stories from my dad’s perspective instead of hers, which I love.