Mes de la Patria (Part II): Where I Belong

And Poetry and Paintings from Kenia Cano!

A month or so ago, maybe two, I was at a party. I had mentioned my Mexican citizenship and at a certain point a US citizen, a long time resident of Mexico, came up to me and asked me why I’d done it. Specifically, he wanted to know, what was the point? As in, what was I getting out of it?

Since September is the mes de la patria, month of independence in which we celebrate freedom from Spain (in 1810), his question comes back to me. And I find myself wrestling with it in funny ways. Though sometimes I wonder why I should. It was one of the first asked on the citizenship application, one of the first asked in the formal citizenship interview. Why do you want to be a Mexican citizen?

I live here. I want to participate in the life of the country, in the community. I feel a bond, a connection.

That’s real. We moved here, with no intention on moving back to the US. We bought our place, the rancho, our land, and we’re involved in different aspects of our colonia’s daily life. We rent a comfortable, big house in centro. It all gives us ties to people, to town and country. So yes.

And of course there’s more. There’s an idea of home. Not just of being here, but belonging. And feeling it belongs to you. Feeling that it sings.

For many years, that was Brooklyn. I was born in NYC, lived in Queens and on Long Island, then Manhattan. After getting married, Katherine and I spent a little time in Rome and Paris, then Virginia. When we moved back to New York in the mid 1980’s, it wasn’t to go back to Manhattan. There was something in Brooklyn. I felt a kind of connection. An energy. I felt a part of a narrative I was only beginning to write. Although for most of our time living in Brooklyn I thought it would be the place I would spend the rest of my life, that narrative was changing. I was changing. So was Brooklyn.

I’ve written before that my first time visiting Mexico, I had an I-belong-here feeling. My experience that time in 1986 was Mexico City, then Oaxaca city and the coast. There came later, longer visits and the realization that the whole country was calling.

But why become a citizen? Why not remain a permanent resident of Mexico? Katherine and I arrived here in September 2016 that way. Why did I make that change?

I think it has to do with changes that were already happening and which my life here has come to accelerate and enlarge. Maybe it’s about my age, maybe the ongoing work of recovery, maybe both. Because what has become most essential to me as a poet, a thinker, a human being, has been understanding and, in some sense, deepening how to see beauty and make meaning out of how I physically, emotionally, and spiritually experience the world

Of course, the physical, emotional, and spiritual are always deeply intertwined. If I’m not physically present, all my senses tuned in to what’s around me, I can’t know a place, I can’t be a part of it. Nor can it be a part of me. Feelings of peace? Tranquility? Release? These can’t happen if I’m unconscious of the space I’m in. For me, the deepest form of any spiritual practice comes down to engagement with the world: people, places, things. ideas. Action. The act of disengagement, isolating myself, the act of cutting myself off from the world and my self, well, that’s kind of death.

Here, in southern Mexico, and throughout the country—though I admit this is less true in the more northern, industrial, desert parts—I feel this engagement, I feel this closeness, I feel this song and this flight. I feel life.

It isn’t just the histories of Mexico, which fascinate me. It isn’t just the poetry, music, art, dance, food, all those things of my everyday life. It isn’t just the sheer physical beauty of the country. It isn’t just the people.

It is all those things together. And then there’s something else, something beyond. A resonance or condition or certainty beyond language. Here I am, a güero, light-skinned, light hair, blue eyes. A New York Jew. I’m obviously different. Except, most times, when it comes to it, no one makes me feel the different as a negative. As an unwelcome other. Rather, my difference has become the difference of affirmation. My otherness as arrival and return. I’m a mexicano gringo.

It has a strange and potent craziness. I feel a funny stirring, despite its violence, when I hear the Himno Nacional. Listening to the presidential press conferences every morning, I feel a kind of pride in nuestra presidenta. September, this our mes de la patria, I fly a Mexican flag on the car.

I like the dynamic changes going on here, culturally, politically, socially. Mexico is a country whose democracy is very messy. In many ways it’s still very embryonic. US media reports talk about cartels and violence. Living here, being here, there’s something else going on. I feel it happening. And it amazes me. Makes me feel proud I can participate in this growth. Growth of a country. Growth of self.

Becoming a citizen was a logical part of the evolution. Physical presence. Emotional connection. Spiritual clarity. I wake up each morning and go through the days with a sense of purpose. And fulfillment. I live in Mexico. I’m Mexican. I belong in it and it in me. I’m home. Like Brooklyn. Just much further south.

Some Poetry:

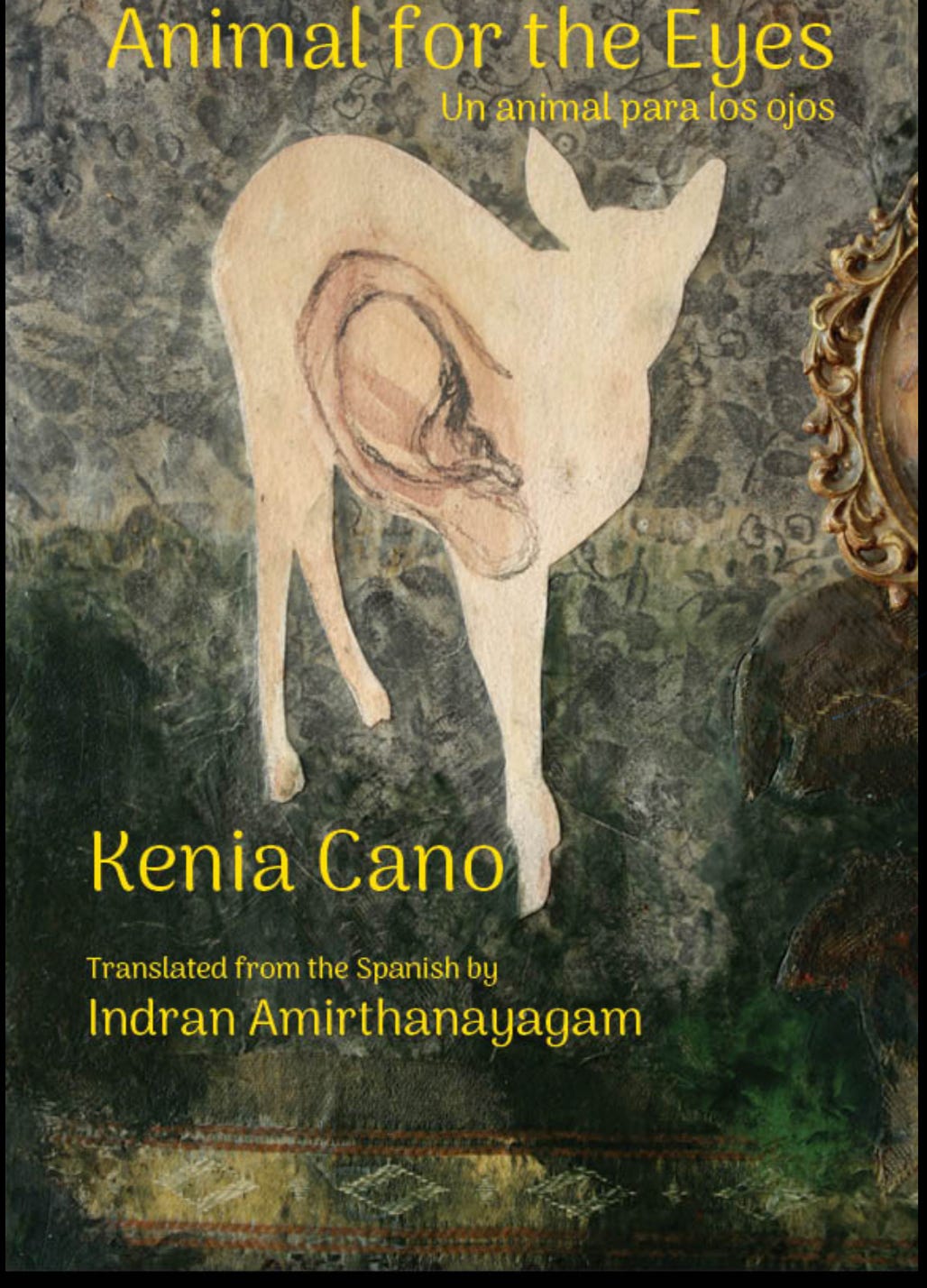

This week’s poet, Kenia Cano, lives in Cuernavaca. That is to say, she is a Poet in Mexico! I first got to know her work through my friend Indran Amirthanayagam—whose poetry has appeared previously in Poet in Mexico—and his translation of her book, Animal for the Eyes/Un Animal Para Los Ojos (Lavender Ink/diálogos, 2025); it first appeared in Spanish in 2009. In that small world way that life works, it turns out she is good friends with Araceli Manzilla Zayas, my friend and poet I’ve also published here and whose book La Casa del Ciervo I’m in the process of translating for 2026 publication. To add to that, Kenia will be visiting Oaxaca at the beginning of October for a reading and I’ll be reading in Cuernavaca for Cuernavaca Poesía, the big poetry festival there, in November. We’re looking forward to hearing each other read and spend a little time together.

Kenia is a wonderful poet and visual artist, who has published numerous books of poetry, is widely anthologized, and whose paintings have been exhibited in Mexico, the US, and France. My small experience of her poetry and paintings is that the work of each deeply informs the other, in ways that are fluid and exciting. There’s an excitement in the power of the image as given by verbal language and by the language of the eye. These originals and Indran’s excellent translations, only give a glimpse of the work she does. I suggest a Google search. I did one and it led me to wonderful places.

On translating Kenia, Indran wrote me this: Transparence is my goal as a translator...and music. I need and want to find a correspondent music in English to what I hear in Spanish. Animal for the Eyes is a delicately sketched, finely filigreed exploration of dark, early childhood memories. I identified with the subject matter, felt a spiritual call to translate these searing poems into English. I have started and slowed down in various manuscripts seeking to move them into English.I managed to get to the end with Kenia's book and I received help along the way from the poet herself. The sweetness born in collaboration, a shared enterprise. Kenia's meticulous editing and fine ear helped me to find the right words in English. Enjoy.

With pleasure I present my (new) friend Kenia Cano to readers of Poet in Mexico.

Kenia Cano, photo Sergio D. Lara

Tu cuerpo vacío me interroga Ese contorno alerta, el hecho de estar siempre sorprendido. Si no es el hueco que deja la inquietud, la incertidumbre de pie: ¿Cuál es tu tamaño necesario? Contesta desde tu muda cueva Voluntad, indícame el camino bajo el entramado silencioso de la madera donde se esconde el insecto nocturno. Your empty body questions me That alert shape, the idea of always being surprised. If not the crevice left by restlessness, uncertainty standing: What’s your required space? Answer from your mute cave Will, show me the way under the silent lattice of the wood where the nocturnal insect hides.

Mordidas de animales que aún no conocemos dentro de nosotros mismos. Filosas marcas del día no agradecido. Una ardilla muerde un trozo de naranja seca. Tiene la cola rala, sin generosidad. Prensada al tronco con sus pequeñas uñas todopoderosas, no se cae, resiste, se alimenta. Un cormorán muerde bajo las aguas del río a un pez cuyo chasquido nos saca del centro. Su movimiento se dirige hacia las profundidades, hambriento, agradece a pesar del miedo. Una mujer muerde una manzana y siente el sabor dulce y bendito de huertos de su infancia. La cáscara del fruto la ha guardado hermosa. Hay mordidas centelleantes de dios que ningún ojo humano comprende. Mordidas que entierran con alevosía sus disparejos dientes sobre la tierra. Vulnerables, con la boca torpe, no logramos sino presenciar. Aún a veces muerdes y no comprendo por qué se nos escapa verte en los ojos expectantes de los muertos. ¿Vendrás a alimentarnos? Bites of animals we do not yet know within ourselves. Sharp marks of the ungrateful day. A squirrel bites a piece of dried orange. Its tail is sparse, ungenerous. Pressed to the trunk with its almighty little nails, it does not fall, it resists, it feeds. A cormorant bites under the waters of the river a fish whose click takes us out of the center. Its movement is directed towards the depths, hungry, it is grateful in spite of fear. A woman bites into an apple and feels the sweet, blessed taste of orchards from her childhood. The peel of the fruit has kept her beautiful. There are scintillating bites of god that no human eye understands. Bites that bury with malice aforethought their uneven teeth in the earth. Vulnerable, with clumsy mouths, we can only witness. Still sometimes you bite and I don’t understand why we miss seeing you in the expectant eyes of the dead. Will you come and feed us?

No quería hablar de la muerte Este sol calienta mi cuerpo imperfecto, alberga lo opaco de mi sacro. Lancé los huesos del ciervo por la ventana: Porosos, amarillentos, ligeros, durmientes ellos también. Lo nuestro ¿Alguna vez fue nuestro? ¿Lo repetirías cien veces? Ella dice que mire sólo este mundo pero lo encuentro vulnerable. Prefiero mirar la palabra cardo sobre el campo que rodea la casa en que trabajo, existe. Existe la huida del gamo, la aparición del colibrí, el perfume del cazahuate. Confío en lo que me dice esta página, en tu ropa blanca, en cada una de tus preguntas. En el lápiz sobre la mesa que esta vez si te detienes a mirar: La estructura molecular del grafito, el fragmento de rama que lo sostiene. Confío en el ritmo, en la asonancia, en la urgencia de quedarte aquí un poco más. I Didn’t Want to Talk about Death This sun warms my imperfect body, harbors the opaque of my sacrum. I threw the bones of the deer out of the window: Porous, yellowish, light, sleeping them too. Was it ever ours? Would you repeat it a hundred times? She says to look only at this world but I find it vulnerable. I’d rather look at the word thistle on the field that surrounds the house where I work, it exists. There is the flight of the fallow deer, the appearance of the hummingbird, the scent of the fiddlehead. I trust what this page tells me, in your white clothes, in each of your questions. In the pencil on the table that this time you stop to look: The molecular structure of graphite, the fragment of the branch that holds it. I trust in the rhythm, in the assonance, in the urgency to stay here a little longer. —Kenia Cano, translations Indran Amirthanayagam, Animal for the Eyes/Un animal para los ojos (Lavender Ink/diálogos, 2025)

Kenia Cano, photo Gilberto Chen

Good Links: Kenia, Aida, and the Himno Nacional

Kenia’s Book!

You can order Animal for the Eyes directly from the publisher. https://www.lavenderink.org/site/shop/animal-for-the-eyes/?v=a906dcd34dae. Or you can support your local independent bookstore. Ask them to order you a copy, and then a few more so others can get it as well!

Aida Cuevas, México en la Piel

This is a lovely version of this very lovely song. Cuevas’ voice soars and inspires.

Himno Nacional Mexicano

The Himno Nacional was written by the poet Francisco Gonzalez Bocanegra with music by Jaime Nunó. It debuted in 1854 and is considered one of the three símbolos patrios (along with the shield and flag). No bouncing ball here, but it does have the words if you want to sing along.

Reasons for citizenship and love of Mexico so beautifully and movingly articulated. Thank you for clearly expressing many of the thoughts and feelings people like me carry in their hearts but find challenging to express🙏. Viva Mexico!🎋

Thank you, Linda. That means a lot! Si, ¡que viva México!